What is an icon, really?

On the signs we use and how we give them meaning

• • •

In our daily lives as designers we often refer to those little simplified drawings we use to convey or clarify meaning as “icons”. Some people call them “glyphs” and others call them “symbols”. We all, of course, intuitively know what they are and what purpose they serve in our field, but we can go a step further in our understanding and clarify how they work, how their meaning is created, and most importantly, how they are interpreted by the intended audience.

To dive into this topic we must first familiarise ourselves with a little thing called Semiotics: The field of study that deals with signs and meaning making. Semiotic theory tells us that icons are “signs”.

What’s a sign then?

Semiotics scholars argue that all communication is a system of signs and the objects they refer to. A sign is anything that communicates meaning, intentionally or otherwise; a thing that refers to another thing. Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure proposed that signs are made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier can be understood as what “carries” the meaning, a.k.a the words we use (whichever form they may take), the sounds we make, our facial expressions, our body language, images, colors, etc. The signified on the other hand is the meaning that is being conveyed, the thing being referred to. This relationship between the signifier and the signified is called signification.

An important thing to consider is that meaning itself can not be communicated, instead we rely on the lived experience of whoever is interpreting the signifier to understand the signified. I can use the word yellow as a signifier, and trust that you will connect that specific word in your mind with the concept of yellow. Sadly, it’s impossible for me to convey yellowness to you if you haven’t already experienced it for yourself. In that sense, Saussure posits that the relationship between the sign and the object is “arbitrary”; meaning that there is no natural connection between, for example, the set of letters that make up the word yellow (y-e-l-l-o-w) and the color they refer to. Any other arbitrary set of signifiers can be used to signify the same object, for instance: Amarillo, 黃, 🟡, and so on.

Understanding signs in this manner allows us to see that meaning is highly dependent on time, place, culture, experience, and the myriad of other factors that make up our individual experiences in the world. This is why signs are open to misinterpretation, while westerners may interpret thumbs up 👍 as generally positive, the gesture can be an insulting or inflammatory for people in Iraq, Iran, Greece, among others. In other contexts the same sign can be used to hitch a ride, or simply make reference to the number one. Cliff Kuang and Robert Fabricant, in their book User Friendly, tell the origin story of the “Like” button; How designers were aware of the possible negative connotations of the sign and how ultimately it was Mark Zuckerberg himself who made the call to use it anyway.

What about icons?

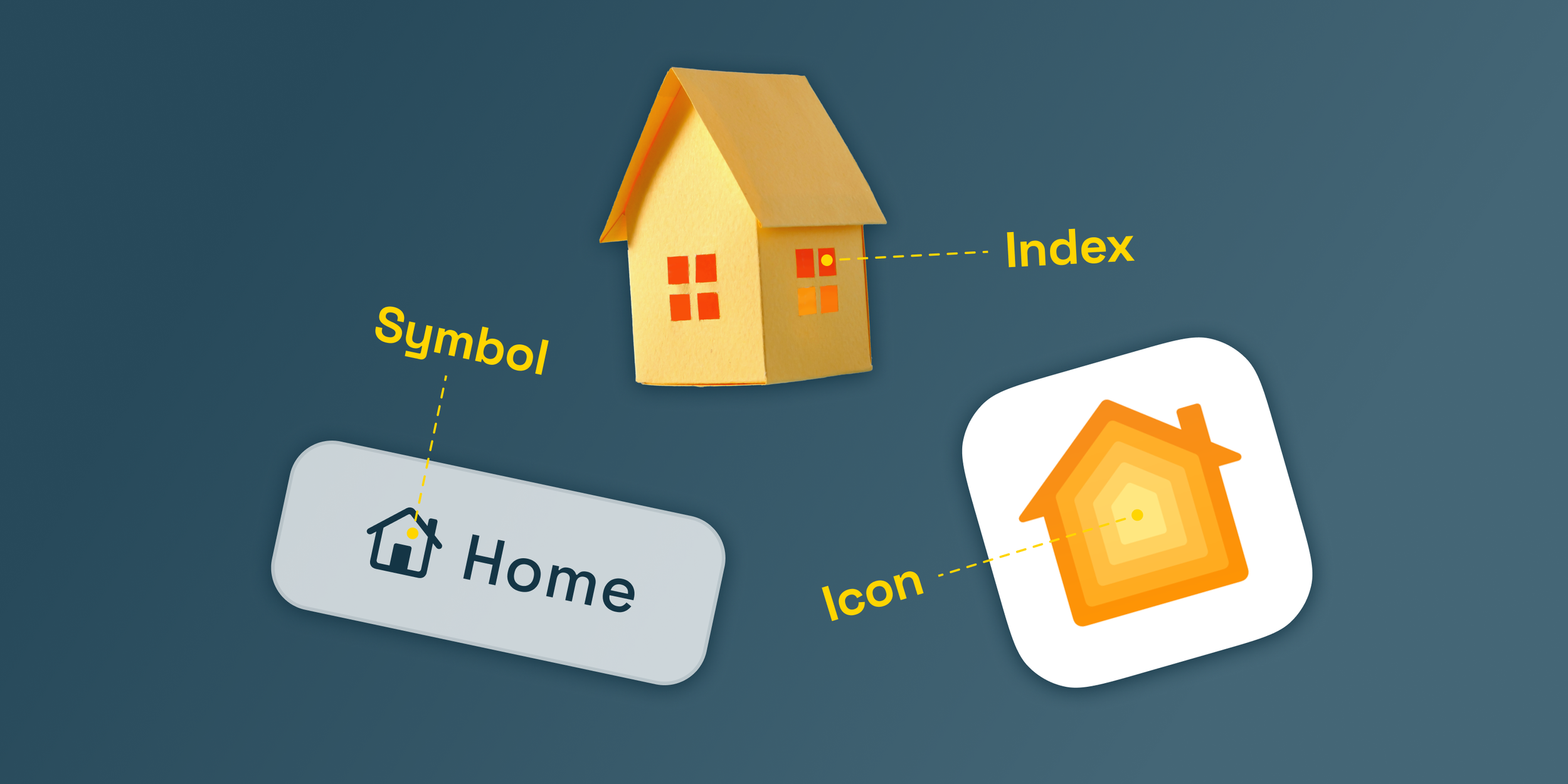

The connection between something like this 🚻 and the word “icon” comes from the work of american philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, about the ways a sign can be further categorized as an icon, an index, or a symbol.

When is a sign an icon?

A sign is an icon if it resembles the object’s characteristics. We can say that 🏡 is an icon for the concept of “House” because it physically resembles a house (or at least a canonical idea of what houses look like), or that ✏️ is an icon for a pencil. I will point out that icons need not be visual, a good example is the haptic feedback your phone gives you when typing on a virtual keyboard. These haptics are an icon for the sensation of typing on a physical keyboard.

Example of an icon

The app icon for Apple’s home app resembles a home physically, and is communicating the concept of a place where people live

When is a sign an index?

A sign is an index if it has a direct connection to the object. The sound of a running water is a sign of a river nearby, the sound of a growling stomach is indicative of hunger, and the smell of frying onions is a sign of delicious food potentially coming your way.

Example of an index

Lights on inside the house indicate people are there

When is a sign a symbol?

A sign is a symbol if it signifies through convention. Take this set of symbols as an example ⏮ ▶️ ⏭, playback controls have no physical resemblance, nor do they have a causal relationship with the actions they perform; their meaning instead is learned through use.

Example of a symbol

The drawing of a house symbolizes the idea of a starting point

When🏡 is not a house

Eagle-eyed readers might point out that when we use the icon for house in User Interfaces we’re not actually trying to convey the idea of a house where people might live, in reality we’re using the sign as a symbol to convey the idea of “home”, the default place from where all activities originate. This is also the case for the pencil, the representation itself is an icon, but place it inside a button and suddenly it symbolizes “edit”

Signs can move from one category to another, my favorite example of this is the floppy disk 💾. It started out in user interfaces as an icon representing the physical object to which files were actually being saved to. As the years passed and the floppy disk fell out of fashion, the icon became a symbol for the action of “saving”, as now people have learned it’s meaning without having actually used a floppy disk (I know, I’m sorry). Another fairly prominent example is the 📞 symbol formerly an icon “phone”.

This multiplicity of signs can be further explained with another concept in semiotics, denotation and connotation. I like to think of it like this: denotation is taking signs literally, connotation is taking them figuratively. Circling back to the 🏡, when we use this sign in a UI we’re making use of the connotation of the sign to provide a metaphor for understanding and improving usability.

It’s not like anyone thinks this is gonna happen if they press the button that says home…

In conclusion

Signs, icons, indices, and symbols are highly contextual and open to as many interpretations as there are people decoding them. Don’t assume everyone has your same understanding of signs, instead we should empathize, test, and validate. Maybe you can avoid insulting a bunch of people with a thumbs up 👍.